. . .as we are the Thirteenth Reinforcements we are doubtless the unlucky ones, according to the superstitious “13”.

Just over a year ago, I travelled across the European farmland that had a hundred years previous reverberated with the sound of mortars and machine guns. I posted here about my great, great-uncle Benjamin Lawn, whose fate was to die and lie buried ‘somewhere’ on the Somme.

On my journey I carried with me a poppy – the symbol that has come to represent the bloodshed and remembrance of the fallen. We in New Zealand wear these on our Remembrance day – Anzac Day – which falls on the 25 April and commemorates our defining moment as a nation at Gallipoli alongside our Australian comrades, although now all battles, including the wars that have followed the Great War are remembered. I had kept this poppy for five months, and carried it across the world for Ben.

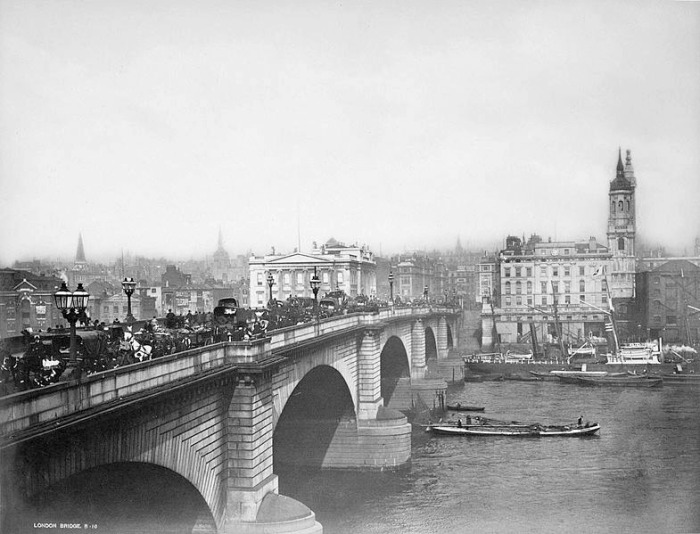

The poppy, a seemingly fragile flower, nevertheless persevered and came to be the first to bloom again in the mangled farmland: it is a fitting tribute to the fallen. Travelling by high-speed train from Paris to Amsterdam and watching the fields of towering ripe corn shoulder to shoulder in the achingly bright sunshine was surreal: a million light-years away from the horrors that happened here. Seated in plush comfort and sealed behind the train windows meant I could not let that single poppy float to the ground, nor place the poppy anywhere: I kept it safe until we arrived in London later that month, 100 years to the day that Ben was killed.

But what exactly had happened to Ben was something that always eluded me as I wrote To Live a Long and Prosperous Life. Many years ago my mother wrote to the New Zealand Defence Force, and enquired about what happened to Ben. I remember seeing the report, and the horror when I realised he had died in the Somme. Yet this report was somehow mislaid and although we both seemed to recall that he was shot, or struck in the head, and that after he was buried the continued bombardment of the area meant his grave was unable to be relocated as all identifying landmarks were obliterated, the frustrating lack of accurate reference material meant that I was unable to write with any accuracy on Ben’s death. Ben’s Army records, now with New Zealand Archives, like other records, does not provide much to confirm or elaborate on his fate.

Papers Past has now filled in the gaps, with further releases of digitised newspapers. For the following excerpts I owe a debt of gratitude to the sleuthing skills of my cousin Peter Walker for providing this information. Peter also contributed significantly to Live Long and Prosper with his research on Ben’s brother John Lawn’s WWI service at Gallipoli.

The first excerpt is from a letter printed in the Greymouth Evening Star on 5th October, 1916. The letter was written two months earlier by Ben on 5 August – he had died on the 27 September. Just one week after this letter appeared in print his parents received notification of his death on the evening of the 12 October and his name was published in the Roll of Honour on Saturday 14 October.

Here, then, is Ben’s final letter home captioned by the newspaper as “Salisbury Plain Camp – A Reefton Boy’s Experiences”:

We have been in this camp since Wednesday week. At Plymouth all the people belonging to the place were at the station to see us. They treated us well, giving buns and tea and plenty of it. The Mayor of Exeter sent us a big bag of cakes each, with a card on each, on which was his name, and wished us a safe return. We arrived at camp at about eight o’clock at night, and the first one that I met whom I knew was Andy McIvor. [Ben’s sister Dinah Lawn had married Sim McIvor, Andy’s younger brother, in 1912) When he saw me he said I had no right to be here. He has not been to France yet. I have been mess orderly and have not done any drill. I hope they won’t keep me back from Ralph and all the boys on account of not doing drill. We were supposed to have been off for the front seven days from when we landed, but owing to an outbreak of measles on our steamer, the Willochra we have been isolated for 16 days. We had about 150 cases, and as we are the Thirteenth Reinforcements we are doubtless the unlucky ones, according to the superstitious “13”. We get leave for three days and most of the boys are going to London. I will, I think go to Cornwall to see Dorothy. [Dorothy James (born 1894), Ben’s cousin, daughter of his aunt Sarah née Lawn] I expect to get there in about eight hours. The distance is about 400 miles, and the trains do go some. We travel at half rates.

We are not tied down so much here as we were at Trentham – we can go anywhere we like within a radius of five miles without a pass. We can travel by motor, but not by train. Ralph and I went for a walk and we got into some big fields and lost out bearings, and we did not arrive until ten o’clock at night. We had to be in not later than 9.30 so we had to go before the commanding officer. Nearly all my mates have joined the machine gun section. They wanted me to join, but I think the infantry will do me.

Alas, the Infantry was to well and truly ‘do’ for Ben.

It was not until many months later that word was received about his fate, underlining how the not knowing must have compounded the grief for family and friends back home and how it was that ‘private’ letters and scraps of information were shared by the publication in the newspapers of “OUR SOLDIERS LETTERS” – the collective noun emphasising the sense of the entire community – and country’s involvement in this Great War.

In the first week of January 1917 William Nicholas (14141), who had been a driver for a carter on Buller Road, Reefton when he enlisted, wrote to his sister, (Mrs Rix of Greymouth) from “Somewhere in France”. This was a welcome letter, received nearly two months later, as he had previously been reported killed, instead of just seriously wounded.

Our company came out of the trenches a couple of days before Christmas. We are billeted in a nice little town, and are having a good time. Our Christmas dinner was a good one. It consisted of roast pork, plenty of vegetables, and an ample supply of plum pudding. All the Reefton boys were together. Minehan, of Cobden, was with us. He was not hurt, as you suppose, but is still going strong. Among our company were Steve Hocking [Blacks Point neighbours of the Lawns, survived the war] and Pal McMasters. The former, having a job at headquarters, is done with fighting for a while. Anyhow, he deserves a spell. He has come right through the campaign without getting a smack. Pal McMasters is in the band. I have not met Jim Hannah, of Boddytown, but am on the lookout for him. Our brigade was relieved for Christmas and New Year holidays, after a long spell in the trenches, and it was up to us to enjoy ourselves a little.

Ben Lawn, of Black’s Point, was not with us. He, poor fellow, was killed while charging the enemy. A piece of shell struck him on the back of the neck. His death was sudden, but painless.

It is a terrible experience to be under continuous fire. Not much credence can be attached to the words of those who say they like it. Those who talk that way have not seen much fighting. I have been in No Man’s Land frequently, small companies having to lie down flat for six consecutive hours on the enemy’s wire entanglements, armed with revolvers, bayonets, and bombs; snow on the ground, and the night bitterly cold. At present we are in the rear seven miles from the front trenches, drilling and route marching all the time. There are many casualties from stray shells, but it is preferable to the front trenches. Building dug-outs, and other kinds of work also has to be done. Indeed, more men are hit in the fatigue parties than the front-line trench, but it is better for the reason that we can occasionally get to town at night. One of Fritz’s aeroplanes will come over and discover some working parties; Fritz receives the report, the result being that the big guns are put on the spot. Of course we do the same. The efforts of the Huns to bring down our aeroplanes are often watched by our men with hilarious laughter and shouts of derision. They will fire 200 shells without a hit. Sometimes we have some close shaves. Our chaps say, jokingly, that they would like to get a “blighty” – meaning a smack – just mild enough to be sent to England. But they cannot be taken seriously, if one is to judge by the manner in which they race for cover when the shells are falling.

We are holding a very quiet part of the line now. The Somme advance, made by our boys a while back, was a hell upon earth. The experience was a rough one. It was in the very place where we are now that the Australians got chopped up terribly. We relieved them when we took over these lines. They advanced and took Fritz’s two front lines. But Fritz was cunning. He let a big dam go in the vicinity, flooding the trenches just occupied by the Australians, and as they clamoured out like drowned rats, Fritz turned his machine guns and shrapnel on them. Even now dozens of them still lie out in No Man’s Land. We send out parties frequently. Forming one of these parties, I have had many peculiar encounters with Fritz. One night we dispatched two Germans sitting on their own wire. This was done through stealthily creeping along in the stillness of the night. Our retreat to our own lines was very hasty and accomplished before Fritz in the trenches had time to recover.

Our rations are good. Porridge in the morning and bacon; good stew for dinner, and bread and butter and cheese or jam for tea. In addition, if desired, plenty of tinned meat. In the trenches a pair of clean sox are issued to us every morning. In conclusion, I think we will all be home for next Xmas. The Germans are beaten. Lately the French have been giving them something to go with. I hope to get a look at Paris before my return. Reefton friends will excuse me for not having time to write.

(Greymouth Evening News, 3 March 1917)

Although Nicholas was nearly 10 years older than Ben it is clear that all the Reefton lads serving knew each other well, as later in the year he again touches on the death of Ben in one of his published letters home. (Nicholas survived the war and returned home in 1919, he died in Auckland in 1959).

Touching the death of Private Ben Lawn, a letter from Private Nicholas to his Greymouth relatives says he was talking to one who was near him when hit. It was during the advance at the Somme that Ben was hit. He dropped and never moved. The writer does not know whether he was hit with a bullet or a piece of shell, but he was killed outright. The boys were going to over to take a Hun trench, but on the way Ben was hit in the neck, and immediately sank. This would be about September 27th. . . Private Nicholas and his friends are still going strong, the latter wishing to be remembered to all friends.

(Greymouth Evening Star, 28th June 1917)

In September 2016, on the periphery of Hyde Park, under some leafy trees just beginning to lose their leaves in the stifling heat of late summer we stumbled upon a memorial to all the animals who have died in British warfare: from pigeons, dogs, to horses and even elephants, here represented in sculpture by two bronze donkeys, labouring to a carry a small cannon and cases of ammunition. Hugely moving, this memorial signals that so many men relied on their beasts of burden, yet their vital role is often over-looked. I tucked what I had come to think of as ‘Ben’s poppy’ into bronze of one of the humble little donkeys, and left it there with the cacophony of the traffic wending its way around Hyde Park, and the hub-bub of shoppers pressing down near-by Oxford Street oblivious to the frozen tableau of the donkey, his shoulders straining forward, his head lifted, in eternaldetermination, as he steps up to serve.

An inscription on the wall reads:

“They had no choice”

UPDATE:

Recently I learned from a family member who visited that Ben’s medals are in the repository at The National Army Museum Te Mata Toa, at Waiouru.

I wrote to enquire about them, and the whereabouts of his ‘Dead Man’s Penny’ which was sent to the next-of-kin of fallen soldiers. I recieved this reply from them:

Dear CynthiaThe medals of Benjamin Webster Lawn are currently on display in our Medal Repository. He received the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. I have attached a photo. We do not have his Memorial Plaque, though.

The medals were donated in 1984 but I am afraid it is not our policy to release details regarding donors.

I would be intrigued to know if anyone knows who had the medals and subsequently donated them.