In December 2017 I spotted a request from Sherri Murphy of Shantytown on the popular Facebook group West Coast South Island history. “I’m am after any information on Albert Lawn” Sherri asked “he had a Barbers shop in Reefton then Hokitika. I especially would like to know the name of his Barbers in Hoki.” Sherri is in the process of re-creating Albert Lawn’s barber shop at Shantytown and the following information we have gathered includes excerpts from To Live a Long and Prosperous Life, West Coast Recollect (sister site to West Coast South Island history), Shantytown and Hokitika Museum archives and descendants of Albert. Perhaps this post will jog a few more memories and bring more information to light.

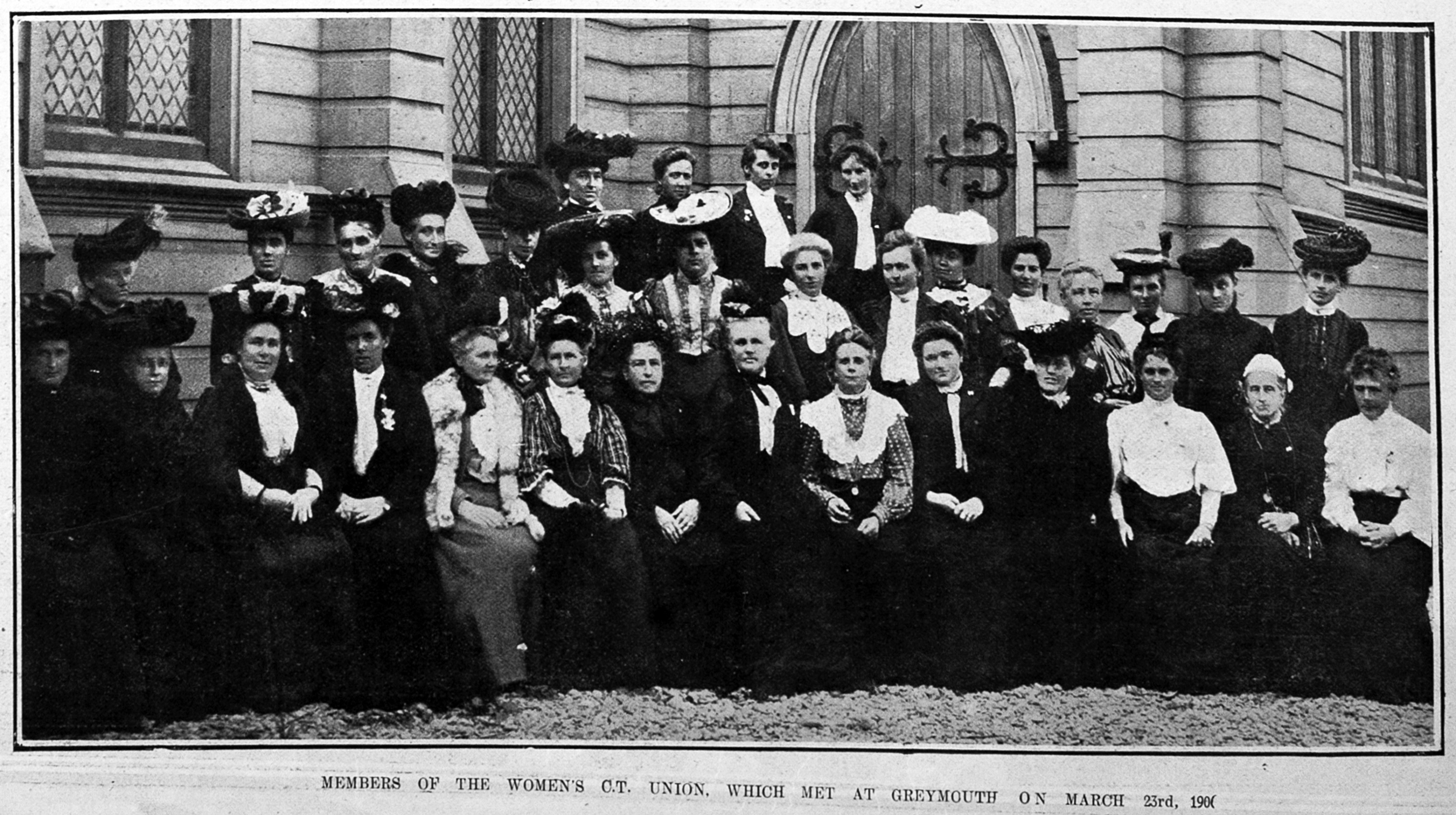

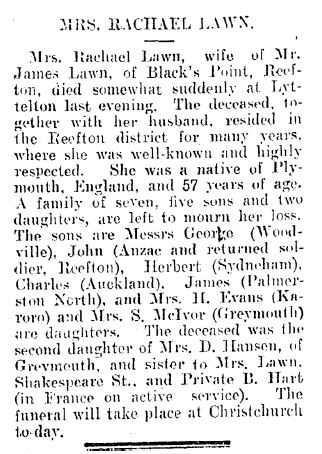

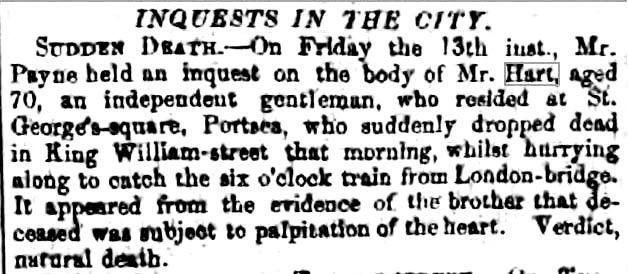

Albert Harold Lawn was born on 9 June 1878, probably at Blacks Point. He was the second son of Thomas Henry and Sarah Esther (nee Hart) Lawn. Thomas and Sarah Lawn had married in Greymouth in 1876 and began married life in Blacks Point, a short distance out of Reefton; Sarah’s precious piano made the journey up the Grey river on a boat, then over the Reefton saddle to the Inangahua river, and again by boat to Black’s Point. Thomas and Sarah soon had their first child, Samuel, who was born the following year in January 1877. He was soon followed by Albert born in June 1878, followed by Norman in 1880.

By the end of 1885 the Lawns were all living in Greymouth again: Thomas and Sarah had moved back from Reefton in 1882 in time for the birth of their son Frank on the first of February, Ernest arrived two years later and Victor in 1887.

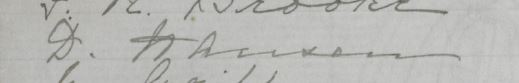

Thomas and Sarah and their family returned to live in Reefton in December 1890. Esther was born in 1895 and Ida was born in 1897. The home of Sarah and Thomas, and their six boys and two girls sat up on the Terrace with a wide verandah at the front. Even though the older boys had left school it seems Sam and Albert both shifted to Reefton as well. Norman was still at school when they came to Reefton, he later attended Nelson College on a scholarship and began work in the Consolidated Goldfields Company, first assisting and then running the assay office. The older boys seemed quite at home in Reefton. . .

. . . In the years to come social and sporting events in the Inangahua Times invariably had at least one Lawn listed as a team member, player or singer contributing. Sarah Lawn continued to fit teaching piano and singing around her growing family, who all learned music as they got older. . . Thomas and Sarah’s eldest sons Sam and Albert Lawn appeared in concerts, Albert playing the auto-harp and Sam the euphonium.

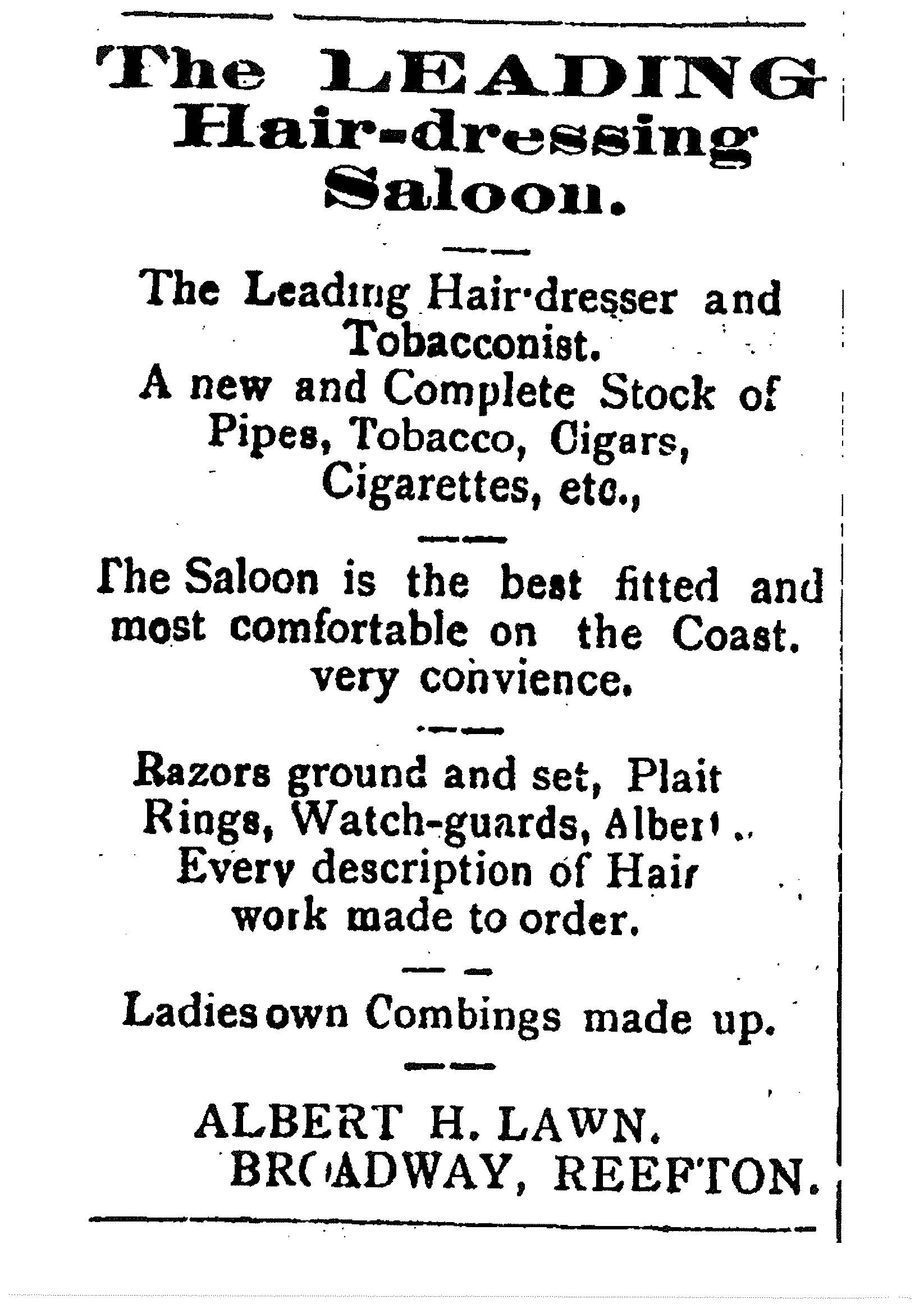

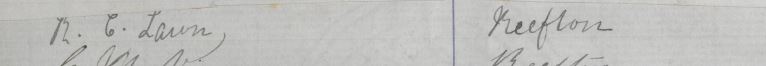

In June 1898 Sarah’s son Albert went into business on his own account when he took over a tobacco shop and hairdressing business ‘The Leading Hair-dressing Saloon’ on Broadway, Reefton where among other things, he ‘made up ladies own combings’ as well as false moustaches and wigs. His profile and a dashing photograph were published in the Cyclopedia of New Zealand (Nelson Marlborough & Westland Provincial Districts) in 1906 (page 251-252) The entries in these were paid for by the contributors, so could arguably called ‘Vanity’ publications, and not always accurate. Albert’s description of his ‘Toilet Club’ has lead to much mirth in modern audiences, although the term ‘toilet’ at the time meant the same as personal grooming.

Albert married Harriet Noble on the 13 November 1901. This event and the extended family photograph has been covered in an earlier post, see Lawn Cousins. In 1902 Thomas Lawn died. Sarah and Thomas’s sons Albert and Norman Lawn both remained in Reefton when their mother and sisters shifted back to Greymouth.

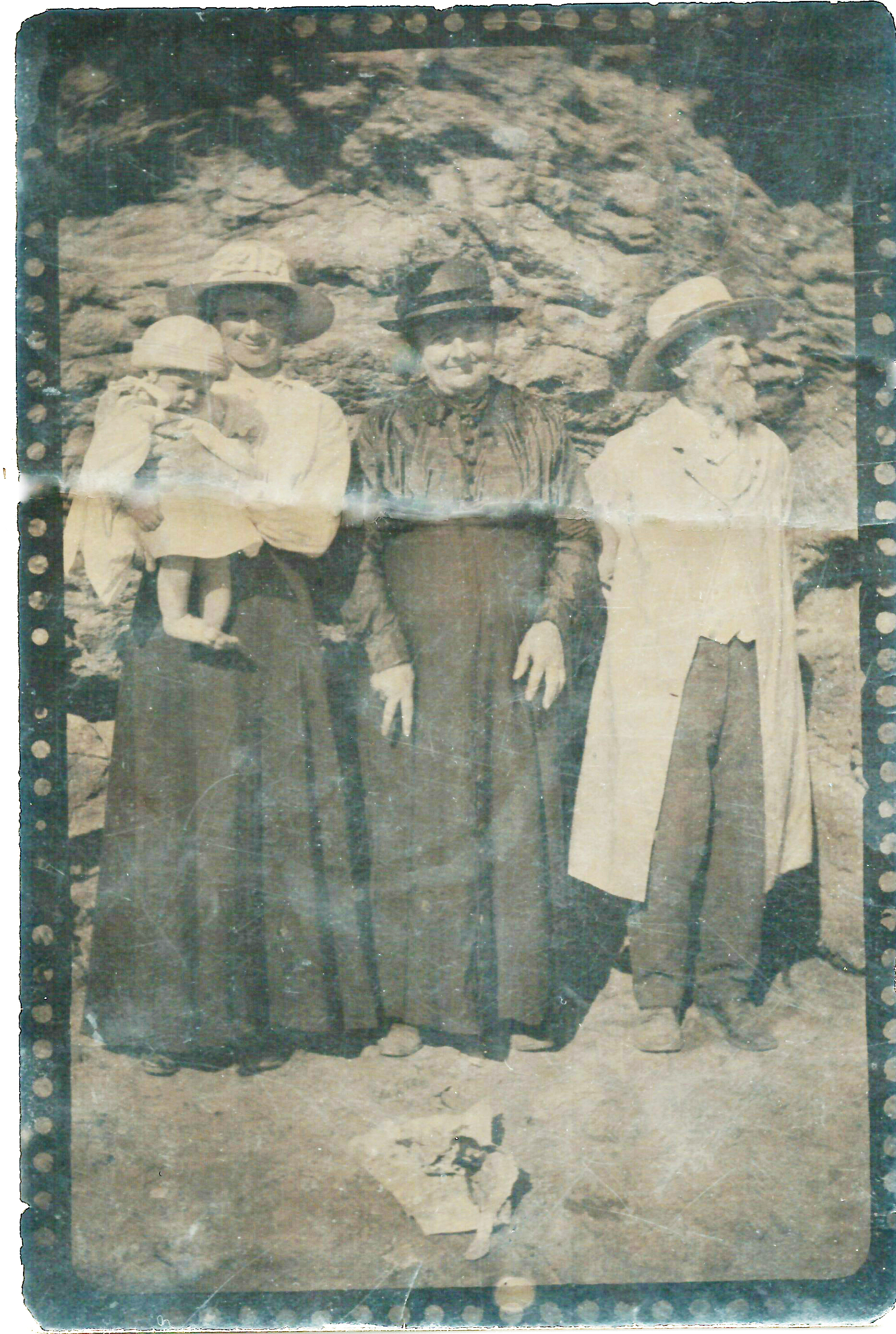

Another photograph survives from this period probably taken mid- to late-1903. It is a four generation photograph, of Albert with his first-born daughter Dorothy (born in December 1902), his mother Sarah and grandmother, Dinah Hansen.

Albert and Harriet Lawn had their second of two children in 1904; family stories recall young Harold visiting his grandmother Sarah and great-grandmother Dinah in Greymouth and taking afternoon tea. The little boy asked if he could have a piece of cake that was on table, and Dinah told him she would tell him when he could have it. Again the little boy asked, and again came the answer ‘I will tell you when you can have it’. To the mortification of his parents, and the astonishment of all others present, in a fit of great daring Harold suddenly snatched the cake off the plate and threw it at Dinah, hitting her in the eye. His father mildly remarked: ‘he was always a good shot’.

LAWN, ALBERT H., Hairdresser and Tobacconist, Broadway, Reefton.

This business was established by Mr. R. J. Simpson and taken over by the present proprietor in June, 1898.

The hairdressing saloon is handsomely equipped with three up-to-date chairs, and every necessary comfort has been provided at considerable expense. Mr. Lawn subscribes to, and places in his saloon, all the West Coast papers and Canterbury weeklies. The shop is well stocked with the leading brands of tobacco, pipes, cigars and cigarettes. The show window is one of the best in the town, and is at all times tastefully dressed. A feature of Mr. Lawn’s business is a toilet Club, with a membership of thirty-five, including some of the principal residents of Reefton. There is a complete tobacco-cutting plant on the premises. Mr. Lawn was born and educated in Greymouth. He served his apprenticeship in Wellington with Mr. L. P. Christenson, a well-known hairdresser and tobacconist of that city.

In 1913, Albert and Harriet moved to Hokitika, where they had a house on the corner of Hampton and Bealey Streets, and Albert opened a shop in Revell Street. One year later was the 1914 outbreak of WWI. Albert was 36 and with two children was graded C in the Reserve Roll. In September 1918 he was reported as seriously ill in the local newspaper and confined to bed for several weeks. His ill health could have passed him as unfit if he was called up, which he was in the ballot drawn in September 1918, published in the newspaper. No official army file exists for Albert, therefore it is likely that he was not actually processed for service.

Grandson Keith Stopforth described what he knew of his grandparents:

In 1913 he moved to Hokitika and opened a barbers shop that he ran with his wife – she sold the tobacco and newspapers at the front of the shop. The shop was always busy with lots of men seated on the long wooden seats down either side of the walls. Some I think were only there to talk. He had 3 or 4 chairs and 2 other barbers helping him. There was an open fire at the end of the shop where men would pass the time of day while they waited for a haircut, a shave or their whiskers trimmed. My grandmother worked in the front of the shop, tobacco sales and cigarettes kept her busy. . .

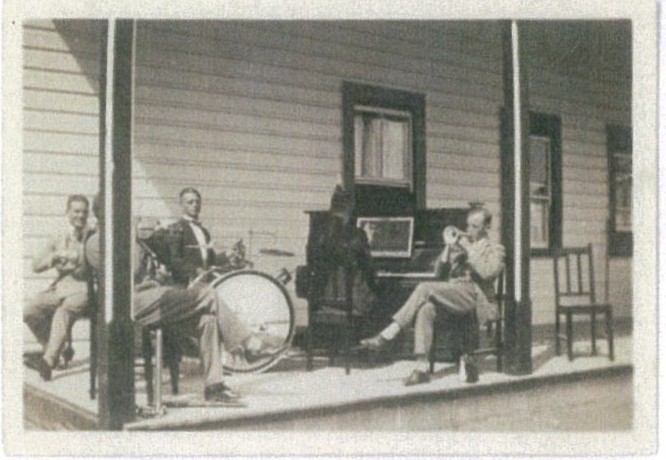

. . . He could play anything to fit the occasion. He had his own band called the Black Hand Band that comprised of two pianists and eight other musicians. He established the ‘Black Hand Society‘ which was a group of friends that gathered together for social evenings. It was exclusive and the yellow badge with the black outspread hand was keenly sort after. [an example of the tin badge in Hokitika Museum (“Beware we never fail”) is red and black]

(Keith Stopforth, 2003 to J. Bradshaw, Shantytown.)

According to Keith, his grandfather had never been taught to play the piano – however this is most likely incorrect, given that his mother Sarah was a music teacher from before her marriage, and almost certainly taught all her children to play along with the many students she tutored throughout her life.

Writing his reminiscences of Hokitika, local man Henry Pierson recalled that Albert’s shop on Revell Street . . . was next door to an old watchmaker called Clark. . . next to that a small lolly shop occupied by . . . Winnie Westbrook. . . Next to Winnie’s was James King Bookseller and Stationer. Pierson continues:

“Albert Lawn, the barber and tobacconist next door to Winnies, used to give us short back and sides for threepence. He was well known for his musical talent and his dance band, the Black Hand, was immensely popular in the 1930s. It gained quite a reputation throughout the West Coast. Because of his great sense of humour, his salon was often the centre of outrageous stories and much hilarity. Some of the town’s local characters came in only to tell a yarn or exchange some tit bit of local scandal to which Albert would respond by adding his own version of the subject.”

(pp 13-15, Pierson, H. (2004) The Crooked Mile: Revell Street as I knew it. Silverfox: Christchurch.)

Great grandson Mike Stopforth adds: The family lived out the back. Nana told me once that they weren’t allowed to go out to the front of the shop and they had to come and go the back way. It was located where the old Supermarket used to be when it was just a four square.

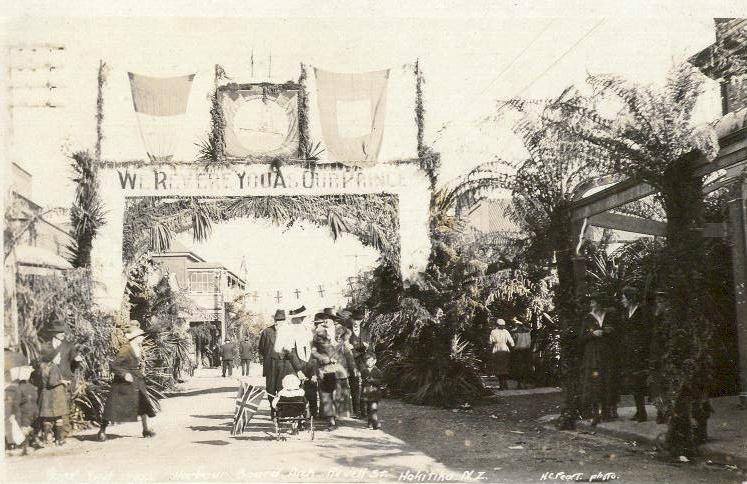

Arguably one of Albert’s ‘proudest’ occasions came in May 1920 with the visit to New Zealand of Edward, Prince of Wales. Arriving on the HMS Renown, in Auckland in late April, he departed Lyttelton, New Zealand at the end of May, enroute for Australia and India.

Preparations for the Prince’s visit to various locations around New Zealand were met with an astonishing frenzy of patriotic excitement, with civic events, triumphal arches (involving large quantities of fern fronds), and hordes of school children and obligatory pretty young ladies positioned to catch the playboy Prince’s eye. Bunting and flags were strung everywhere, children wrote essays and holidays declared. The newly formed RSA were hopeful to have their building officially opened, and returned servicemen were lined up to be presented with medals. In Greymouth, a young man Mr. R. G. Caigou of the Public Works Department spent hours laboriously painted an illuminated address to be presented to HRH by the Mayor on behalf of the citizens (see bottom of this post for an image of the address). This young man became Albert’s brother-in-law when his sister Esther married Russell Caigou in Greymouth, in January 1921.

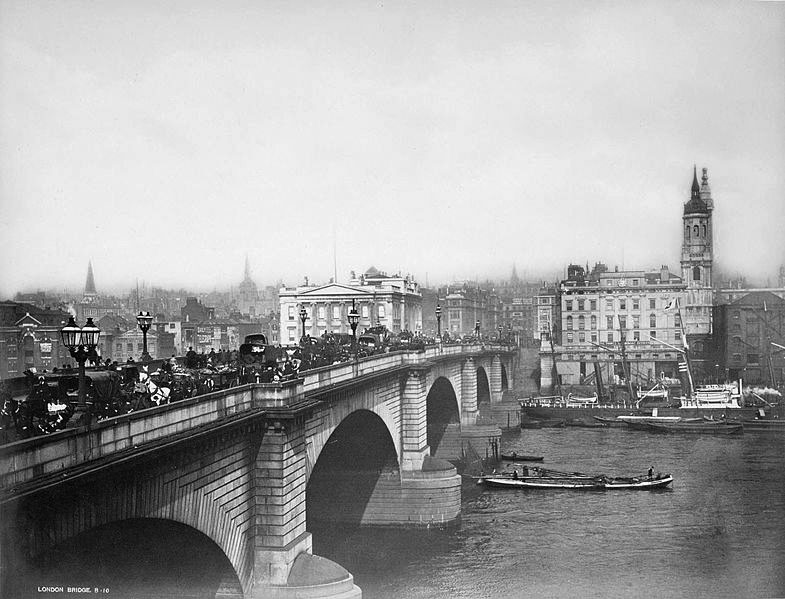

The visit of the Prince to the Coast was somewhat fleeting: he came by train as far as he could from Nelson, motored to Westport, then back to Reefton in a motorcade of 30 cars that included being ‘filmed for the cinema’ passing through fern arch on the Buller. (The press car ended up upside down in a ditch full of blackberries before it reached Reefton). On the 12 May the Prince went by train from Reefton to Hokitika, where he spent the night and then to Greymouth the next day before heading to Christchurch. Details of events of the tour were reported in newspapers all over New Zealand (and overseas).

In Hokitika on the night of the 12 May a grand ball was held in his honour. The Black Hand Band played and after the event the members were greeted by the Prince and shook his hand. According to Keith Stopforth the Prince was so intrigued by the name [of the band] that he enrolled as an honorary member of the Black Hand Society.

The following was originally published in the Melbourne Age:

“PROMENADE YOUR PARTNERS”

AND THE PRINCE DOES SO. A HUMOROUS PICTURE A delightfully humorous picture of the ball given at Hokitika in honour of the Prince of Wales was cabled to the Melbourne Age by one of the correspondents with the Royal party. He said: “The ball at Hokitika was an enormous popular success. After a public reception the Prince, attended by his staff, proceeded to the ball, which began at 10 o’clock. Most of the young men attending wore tweed suits. One old gentleman wandered through the happy throng wearing a long overcoat dating back to the period when “Bully” Hayes used to make Hokitika a favourite port of call when returning from his predatory expeditions among the islands. Another elderly dancer appeared in tweed trousers and a Cardigan jacket buttoned tightly around the throat. The ladies devoted more attention to dress than the Hokitika men. Many were accomplished dancers, and the Prince danced vigorously with a succession of Hokitika girls. In the official set, which opened the ball, Mrs R. J. Seddon, widow of the late democratic Imperialist, took part. The Prince danced in the set with Miss Perry, the Mayor’s daughter. A dance or two later the master of ceremonies, taking the middle of the floor, issued in a loud word of command, ‘Promenade your partners for circular waltz.’ The Prince does not care about waltzing as a general rule at balls which he attends, and he frequently exercises the Royal prerogative of cutting waltzes out of the programme, substituting one-steps or fox trots. At Hokitika, however, he promenaded his partner, according to directions, with the rest. Supper was an immense success. Rising early, a cool breeze from the snowclad mountains refreshed overnight revellers. From the hotel windows one could see Mount Cook, covered with snow apparently overlooking Hokitika, but in reality many scores of miles away.

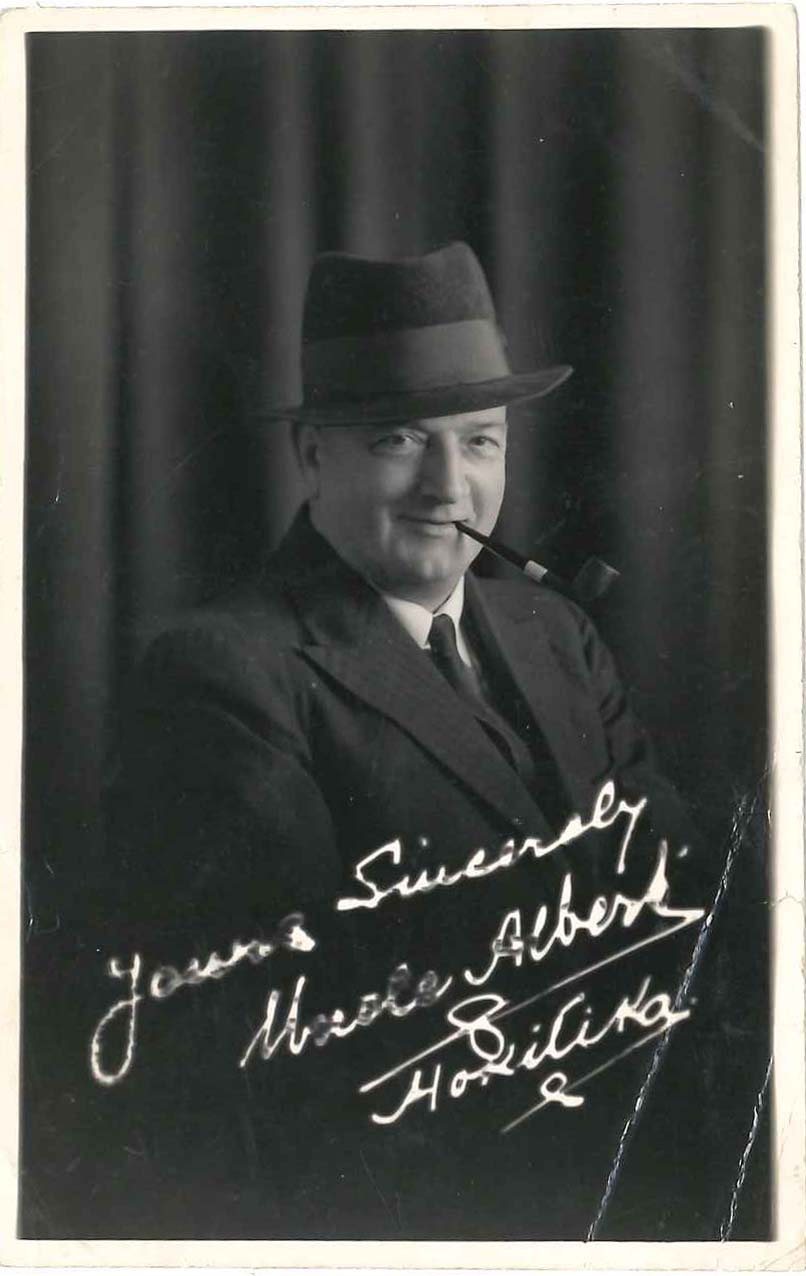

In later years Albert became a radio announcer and had his own children’s session once a week from Hokitika on Thursday nights. Known as Uncle Albert he was obviously very popular as he had a studio photograph that was given out to his listeners. A copy of this photo, cropped without the inscription is in the HLR collection – it wasn’t until Sherri shared this image that I realised that this was Albert Lawn in later life.

“In Weld Street , Hokitika, was the studio . . . “Uncle Albert” was the man children came to love. Uncle Albert was gifted with his hands – not just for his daily job of haircutting, but as a pianist who had learnt to play by ear. One of his proudest occasions would be when the Duke of Windsor [sic] visited Hokitika in the 1920s – Uncle Albert being the official pianist as a member of the Black Hands [sic] Orchestra.

He was often heard on Mickey Spier’s 3ZR Greymouth radio station conducting sessions with Donald McLeod, a well known identity who possessed a phenomenal memory. Within the space of seconds Donald would answer any questions, including trick ones, relating to events and dates, he was seldom wrong. Also joining “Uncle Albert” as he was known to radio listeners was ‘Aunt Dorothy’ (Jock Robinson) a talented pianist of Hokitika.

Bill Dwan served his apprenticeship with Albert Lawn, until he left to open his own business in Weld Street. Ron Brown, another of Albert’s apprentices, opened his own shop in the Regent Theatre corner shop.

After Lawn’s barber and tobacconist shop had closed down, Don Ramsey conducted a radio and records business in it for some years.”

pg 26 Looking at the West Coast, August 1965

A staunch Labour party supporter, he represented the Blind institute on the West Coast for many years. After suffering from diabetes for some time, Albert lost his left arm to the disease.

Understandably this was devastating for him as it meant he was no-longer able to work or play the piano, although there is one account of him wearing a prosthetic limb so he could play chords on the piano. However, family reported he sunk into a deep depression, from which he never truly recovered.

Albert Harold Lawn died in Hokitika on 22 April 1952, aged 72. Harriet lived until the age of 82, until she died in 1961. They are buried together in Hokitika.

Update September 2020:

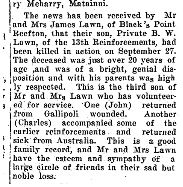

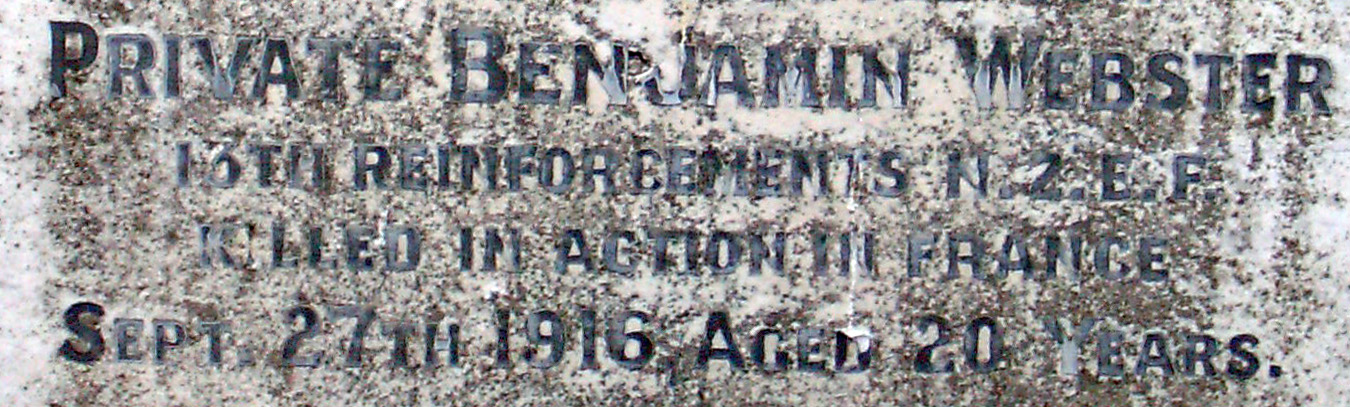

For once, the rain had stopped, and as one account described, the weather was glorious, and was excellent for aviation work. First the artillery bombarded the enemy, and then a creeping barrage, with artillery fire moving forward in increments and the troops followed behind—although sometimes the troops were too enthusiastic, got too far ahead or the creeping barrage was off range and men were killed by ‘friendly fire’. The men were ordered over the top at 2.15 pm on 27 September. It was overcast and rainy: the fine weather had not lasted. The 1st Canterbury Battalion advanced behind the barrage, with the 12th and 13th (Ben’s Company) in that first wave. The official account concludes the description of this offensive:

For once, the rain had stopped, and as one account described, the weather was glorious, and was excellent for aviation work. First the artillery bombarded the enemy, and then a creeping barrage, with artillery fire moving forward in increments and the troops followed behind—although sometimes the troops were too enthusiastic, got too far ahead or the creeping barrage was off range and men were killed by ‘friendly fire’. The men were ordered over the top at 2.15 pm on 27 September. It was overcast and rainy: the fine weather had not lasted. The 1st Canterbury Battalion advanced behind the barrage, with the 12th and 13th (Ben’s Company) in that first wave. The official account concludes the description of this offensive: